By Laura Riley

Laura Riley is a Lecturer-in-Law at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law, Los Angeles, California.

“The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons”

– Fyodor Dostoyevsky

No more than a month after President Donald J. Trump came into office, his newly appointed Attorney General, Jeff Sessions reversed1 an executive policy established by the Obama Administration2 only six months prior, reducing federal use of private prisons. Around the same time, two classes of what could be 60,000 immigrant detainees sued one of the federal government’s biggest private prison contractors for using them as forced labor and other abuses.3 Sessions’ reversal of the private prison phase-out makes it clear that the current administration does not acknowledge a link between private prisons and civil rights violations. Indeed, Sessions’ reversal ensures continued harm4 by continuing to fund5 such abuses.

The Trump Administration’s about-face brings the humanitarian crisis underlying the private corrections industry into plain view—or, at least it should. With the current administration’s refusal to deal with civil rights violations in private prisons it is up to the people of the United States to notice and respond to the civil rights abuses that occur within the privatized criminal justice system—a system rooted in our country’s racism and anti-immigrant sentiment. If we don’t, we will soon arrive at a new height of injustice.

This article presents a brief history of the United States’ use of private prisons, which has been relatively short in duration when compared to its other longstanding penal schemes and systems. It will also introduce the major private prison corporations and analyze their market share and strategies, with particular focus on how these corporations’ political contributions affect that market share. Next, it looks at the human toll wrought by these companies over the past decade, examining the various civil rights violations that have occurred at private prisons as well as the litigation ensuing from those abuses.

It will then examine and compare the Obama Administration’s phase-out policy with the Trump Administration’s revised stance. These approaches will be viewed side-by-side with stock price comparisons of the major private prison companies, which will reveal the effects that certain political milestones—specifically, Trump’s election and his administration’s major policy announcements—have had on private prison stock prices.

The Trump Administration’s reversal of the private prison phase-out in fact only serves the business interests of the private prison companies that support the Trump Administration. The article further contends that the Trump Administration’s promise to continue contracting with private facilities will only exacerbate existing civil rights violations within those detention and prison complexes.

An overview of private prisons and incarceration rates in the U.S.

In 1925 the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics began recording the number of persons sentenced to state and federal correctional institutions.6 In 1981 it released a report that analyzed the annual increase of incarcerated individuals over the prior sixty years. This report revealed that the average annual increase in incarceration was 2.4 percent, a rate that increased dramatically to 7.1 percent beginning in 1974.7

However, in the early 1980s, two the largest private prison corporations, CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America, herein referred to by its New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) symbol “CXW”)8 and GEO Group, Inc. (GEO),9 were founded. Shortly thereafter in 1983, CXW secured its rst contract with the federal government to design and construct a so-called “Processing Center,” an immigration detention facility, for Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) in Houston, Texas.10 Four years later, GEO received its rst government contract.11

Coinciding with the early rise of prison privatization, in 1984 prisons experienced inmate population growth of nearly 6 percent—despite prior judicial interventions aiming to prevent facility overcrowding.12 The Bureau of Justice Statistics report mischaracterized the 6 percent increase as “sharp growth.” The increase was the same as the year prior (5.6 percent) and only half the rate of growth for the years 1981 and 1982 (12.2 percent and 11.9 percent, respectively).13 Put more simply, the 6 percent growth was a marked downturn when compared to prior years.

Over the next two decades, the number and percentage of individuals in the custody of private prison and detention facilities continued to increase. By 2015, the most recent year for which there is data available, the Bureau reported that there were 91,300 individuals in the custody of privately- operated state prisons and 26,000 people in the custody of privately-operated federal prisons.14 These numbers account for over 7 percent and 13 percent, respectively, of the incarcerated population nationwide.

Major Industry Players

The three major corporate players in the private prison industry are, in order of market share, CXW, GEO, and the privately held Management and Training Corporation. Together, these companies control 62 percent of the industry’s $5.3 billion annual revenue in the U.S.15 The remainder of this article will focus exclusively on CXW and GEO, the two largest private prison companies, both publicly traded. In 2016, CXW had a 34.9 percent market share of the private prison industry revenue and GEO had 27.1 percent.16 Since GEO’s founding in 1988, there is small risk of new private prison market entrants gaining market share control because of high capital costs to enter the industry, accreditation requirements, and government regulations. Market concentration has only continued to solidify over the past two decades. In 2010, for example, GEO acquired a former industry player, Cornell Companies.

Although the major industry players’ market control has only increased, the private prison industry does face some risk. First, for much of the public the notion of a private prison company has the same immeasurable “ick” factor of a for-pro t school. Moreover, although as Alexander Volokh remarked that “there is no systematic information about [public] reaction to prisoner abuse in public and private prisons,”17 one indicator of public hostility towards private prisons is that, in correctional facility abuse cases, juries have been more willing to award large verdicts against corporations than against governments. Second, private prison facilities, as Deputy Attorney General for the Obama Administration Sally Yates once stated, “simply do not provide the same level of correctional services, programs and resources …[and] they do not maintain the same level of safety and security.”18

For these reasons, the Obama Administration issued his executive order phasing out federal private prison contracting in late 2016. After the announcement of the phase-out plan, but before the 2016 Presidential election results, IBISWorld released a Correctional Facilities report noting that the market for private correctional services tended to be immune from economic cycles because their revenues stem from state and federal contracts.19 Therefore, private corrections corporations more readily withstand market fluctuations normally experienced in private industries. Despite such insulation, the report rated corrections market volatility as “medium,” since it is affected by judicially-imposed changes to sentencing practices and mandatory sentencing schemes, as well as phase-out policies such as the one implemented by the Obama Administration.20 Indeed, as noted by the ACLU, “in a 2010 Annual Report led with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the largest private prison company, stated:

‘The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by

…leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices…’”21

In response to these market risks, it is unsurprising that CXW and GEO have increased their political spending. Since the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission,22 public corporations do not have to disclose their political donations. Despite calls for corporate transparency from investors and advocacy groups, there is no requirement that companies like CXW or GEO disclose any information regarding their political contributions.

Yet we know that corporations make sizeable contributions to promote their business interests.23 The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reports that CXW “alone spent over $18 million on federal lobbying between 1999 and 2009” and that “[b]etween 2003 and 2011, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics, [CXW] hired 199 lobbyists in 32 states… During the same period, GEO hired 72 lobbyists in 17 states.”24

CXW and GEO also spend money combating industry reforms. IBIS- World reported that CXW and GEO jointly spent over $1.5 million fighting against the Private Prison Information Act,25 which would have subjected private correctional facilities to the Freedom of Information Act in the same way as government-run prison and detention facilities.26 Moreover, CXW and GEO have their own Political Action Committees (PACs) that funneled $218,700 and $454,700, respectively, into the 2014 mid-term election cycle.27 USA Today reported that GEO gave $225,000 (through one of its subsidiaries) to a super PAC focused on electing Trump and, later, directly gave $250,000 to Trump’s inauguration.28 CXW likewise contributed $250,000 to Trump’s inauguration.29

The Trump administration has welcomed the financial support of these major corporate players, a self-interested and insidious move on Tump’s part. Beyond the financial incentive to encourage the growth of the private prison industry, Trump and his administration use punitive rhetoric towards those groups most affected by privatization (through increased immigration enforcement and harsher criminal sentences). As evidenced by the examples of private prison abuses described below, a link between private prison growth and human rights abuses has emerged. Acknowledging this link is essential to improving litigation, lobbying, and policy efforts aiming to counteract this trend.

Human impact of private prison businesses: Lowlights and lawsuits

The crucial critique that civil rights advocates levy against the private prison business model is that the greater number of immigrants and inmates who are detained and/or convicted, the higher the demand for these companies’ products and services. Accordingly, private prison corporations have a financial incentive to ensure that increased (and prolonged) detention and convictions occur. They also have “perverse incentives to maximize profits and cut corners—even at the expense of safety and decent conditions,” which “may contribute to an unacceptable level of danger in private prisons.”31

See note 30

First, corporations may cut costs by hiring non-unionized prison staff, providing only minimal healthcare to inmates and detainees, and/or allowing facility overcrowding.32 Second, private prisons contractors may also pay their non-union employees less than their governmental counterparts.33 As a result, the companies have higher worker turnover, which may be one of the causes of increased prison violence behind and across bars.34

These cost-cutting measures undermine the safety of prison staff and those who are incarcerated. Indeed, as exemplified by the numerous lawsuits detailed below, the elevated human risk attendant to the privatization of the penal system is unacceptable.35

Both CXW and GEO have a history of being sued for the egregious and ongoing abuses that have occurred at their facilities. The charges against them range from criminal neglect and sexual violence to, more recently, unjust enrichment due to the forced and coerced labor of inmates. The ACLU’s report “Banking on Bondage: Private Prisons and Mass Incarceration” describes many of these lawsuits, but there are others.36

In one case in 2000, GEO was ordered to pay $42.5 million to the family of Gregario de la Rosa, who resided in one of GEO’s Texas facilities.37 The jury found that prison officials stood by while de la Rosa was beaten to death by other inmates.38 The extent of the abuse and GEO’s attempt to cover it up resulted in one of the largest punitive damages ever awarded against a private prison company.39

In 2007, GEO settled a lawsuit brought by the Texas Civil Rights Project on behalf of LeTisha Tapia’s family for $200,000.40 In that case, 23-year-old Tapia was held in a cell with male inmates. She reported being raped and beaten. Subsequently, she hanged herself.

In 2008, a GEO prison administrator pleaded guilty to federal charges that she “knowingly and willfully [made] materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statements to senior special agents”41 by covering up GEO’s pervasive and improper hiring of prison guards—nearly one hundred had not received mandated criminal background checks.42

More recently, in 2014, detained and formerly detained immigrants sued GEO for wage theft and civil rights violations stemming from one of GEO’s ICE-contracted facilities. Specifically, the violations were non- compliance with Colorado minimum wage laws, forced labor under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, and unjust enrichment based on these violations.43 The second and third claims survived summary judgment and on February 27, 2017, a federal judge certified the class of plaintiffs as to these claims, allowing as many as 60,000 un- and undercompensated immigrant detainees to move forward with their suit.44 If the case continues to move forward it could both allow for as many as 60,000 immigrant detainees to be compensated for their forced labor and disrupt the economic incentives private prison companies have with involuntary labor.

Such inhumane practices are neither accidental nor incidental to a capitalist ethos of cost-savings. They deliberately criminalize immigrants and marginalize black and brown communities, in turn leading to fewer immigrants on the path to citizenship and more disenfranchised people of color. But abuse within the private prison industrial complex is not limited to the prisoners. Private prison staff have also experienced their share of exploitation and violence.

For example, in 2013, CXW (then Corrections Corporation of America) was found in civil contempt of a settlement agreement it had reached with a class of prison staff for failing to fill positions that were mandated to be filled under its contract with the Idaho Department of Corrections.45 The deficiency arose out of CXW’s falsification of staffing records in order to cover up the staffing shortages which had created safety concerns.

That same year, GEO also entered into a settlement agreement46 with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) as a result of allegations of serious workplace violence issues at GEO’s East Mississippi Correctional Facility. The settlement required GEO to hire a third party corrections consultant to, among other things, audit the adequacy of staff plans, conduct a workplace hazard assessment, develop and implement a Workplace Violence Prevention and Safety Program, and provide employee training.47 These requirements extended to GEO’s correctional and adult detention facilities nationwide.

In 2013, GEO also paid $140,000 to settle a sexual harassment lawsuit brought by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and Arizona Civil Rights Division on behalf of female employees.48 The civil rights groups alleged that GEO “had an extreme tolerance for sexual harassment” at a prison facility in Florence, AZ and that “male managers at GEO sexually harassed numerous female employees and fostered an atmosphere of sexual intimidation” through multiple and ongoing incidences of serious verbal harassment and physical harassment.

Although litigation and settlement agreements can serve as effective enforcement mechanisms for protecting prisoner rights on a long-term basis, there are limitations. Occasionally, subsidiary corporations do not comply with their parent corporation’s obligations. Likewise, sometimes a prison corporation will fail to monitor its subcontractors. This occurred in 2016, when GEO’s private medical contractor, Corizon Health, settled with several prisoners for approximately $4.6 million. In that case, one of Corizon’s doctors provided medically unnecessary rectal examinations and inadequate medical care amounting to multiple instances of sexual assault.49 These civil rights violations led the Obama Administration to formally phase out the use of private prison contractors.

Obama administration policy & stock price effect

As discussed above, on August 18, 2016, then-Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates issued a memorandum reducing federal use of private prisons,50 signaling a shift in the Obama Administration’s prior use of private prison contracts.51 In her memorandum, Yates stated: “I am directing that, as each contract [with a private prison corporation] reaches the end of its term, the Bureau should either decline to renew that contract or substantially reduce its scope in a manner consistent with the law and the overall decline of the Bureau’s inmate population.”52 The release of this memorandum had a substantial impact on CXW and GEO. Each experienced a significant decline in stock value following its release.53

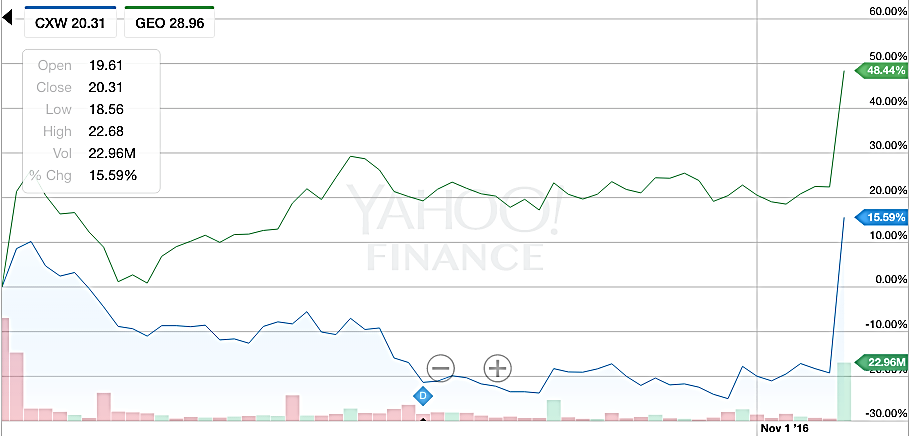

Stock Price Comparison from August 18, 2016 – November 8, 2016

However, after the Yates memorandum, the graph above reveals that, CXW’s and GEO’s February 2017 stock decline not only leveled off but regained and surpassed their initial values after Trump’s election.

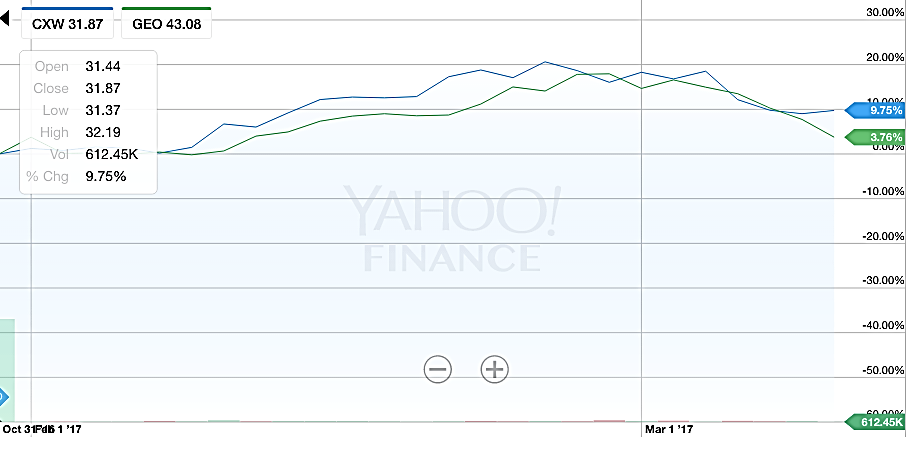

Stock Price Comparison from 2007-2017 (Obama First-Term – Trump Election)

And, as demonstrated above, over the course of ten years leading up to Trump’s election, the major players in the private prison industry experienced overall growth. However, the spike after Trump’s election proved remarkable.

Stock Price Comparison from November 8, 2016 – March 8, 2017

Furthermore, CXW and GEO’s stocks have only continued to increase since Trump’s election,54 spurring multiple news outlets to describe Sessions’ reversal as a victory for CXW and GEO.55 In a way, those media outlets were correct—CXW and GEO stock prices peaked around the date the Justice Department withdrew the phase-out policy. This can be seen most clearly in the chart below, which tracks CXW and GEO stock values between Trump’s Inauguration and March 1, 2017. (Notably, while the stock prices went down slightly in the days following Attorney General Session’s February 23 announcement, they were still up from their pre-election values).

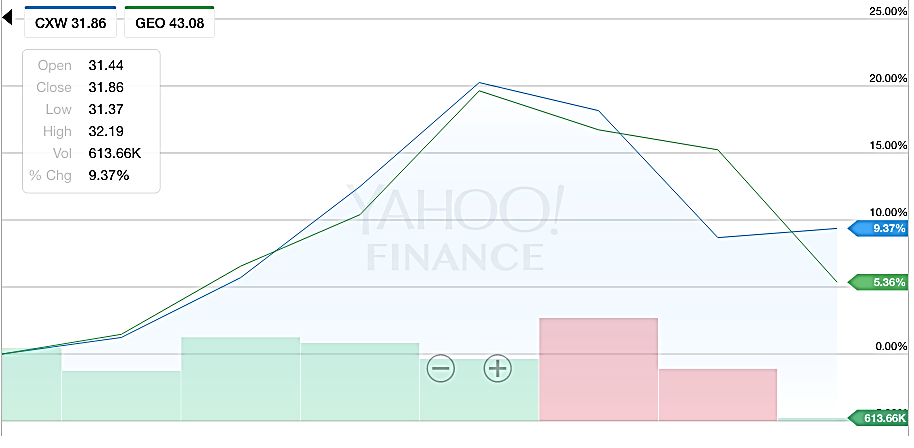

Stock Price Comparison from January 20, 2017 – March 1, 2017

It is important to note that the initial appreciation in private prison stock prices and subsequent decreased volatility reflects a greater likelihood that the federal government will grant new CXW and GEO contracts. As the market predicted, in April 2017 the Trump Administration awarded a $110 million contract to GEO to build a 1000-bed immigration prison facility.56 The risk of revenue loss that CXW and GEO faced as a result of the Obama Administration’s phase-out policy has been lowered, if not entirely eliminated. The future thus seems bright for the private prison industry—at least for now.

Business risks and rewards, civil rights opportunities and threats

Businesses examine operational risks and rewards.57 In light of the changing political climate surrounding incarceration, industry giants such as GEO and CXW have largely shifted from a defensive position of lobbying and opposition, to an offensive one. As the Trump administration has made clear—by accepting political donations from CXW and GEO and by its retraction of the Obama Administration’s commitment to phase out private prisons—the private prison industry, faces no political threat to its growth objectives from the Executive Branch. In addition, the private prison industry no longer has to concern itself with the Obama Administration’s sentencing reforms that eliminated or reduced sentences for certain drug crimes and moved away from incarceration for non-violent crimes—reforms that vitiated the need for new prison facilities.58 Even so, the private prison industry still faces opposition.59

Corrections U.S.A., the largest organization of public correctional officers in the country, represents approximately 80,000 public prison officers and touts itself as the “leader in the fight against prison privatization.” The company furthers its stated position against prison privatization by supplying members with educational materials to organize around fighting the privatization of prisons.60 Its mobilization efforts could help sway public perception, along with its federal lobbying and PAC activity could sway certain legislators, in ways that would be unfavorable to CXW and GEO.

In addition, some civil codes, like the California Civil Code,61 exempt the government and its subdivisions and agencies from punitive damages. This exemption does not apply to private contractors, such as CXW or GEO, which has permitted large jury verdicts against such companies. Large punitive damages can mean a big hit to the company’s bottom line.

Finally, assuming that, in a democracy, politicians represent the will of the people, public perception may have its effect on Executive Branch policy by way of the 2018 mid-term elections.62

Conclusion

The Reason Foundation, a Los Angeles-based research organization, estimated that outsourcing incarceration to private prisons could cut the cost of housing inmates up to 15 percent.63 We should consider why this might be the case. These savings would not be the product of efficient operations. History teaches us that they would be the result of forced labor practices and a failure to provide the number and qualify of staff required to provide a safe living environment.

With the Trump Administration’s guarantee of continuing contracts with private detention centers and prisons, human harm in such centers will only continue to increase. Although civil rights advocates are making great strides through their use of innovative legal theories that connect conditions of confinement to the perverse economic incentives within the industry, we must continue to demand transparency of the private prison industrial complex in order to slow its growth and its abuses.

___________________

NOTES

- As reported in, among other outlets, Matt Zapotosky, Justice Department Will Again Use Private Prisons, WASH. POST (Feb. 23, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/justice-department-will-again-use-private-prisons/2017/02/23/ da395d02-fa0e-11e6-be05-1a3817ac21a5_story.html?utm_term=.62a290273603.

- Memorandum from the U.S. Dept. Justice Office of Deputy Attorney General to the Acting Director Federal Bureau of Prisons (Aug. 18, 2016), available at https://www. justice.gov/opa/file/886311/download.

- See, e.g., Alene Tchekmedyian, Thousands of Immigrant Detainees Sue Private Prison Firm Over ‘Forced’ Labor, l.a. TImeS (Mar. 5, 2017, 5:00 AM), http://www.latimes.com/ nation/la-na-immigrant-workers-20170305-story.html. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (“TVPA”) 18 U.S.C. § 1589, the basis for one of the claims that was certified in a class action, makes it unlawful for anyone who “knowingly provides or obtains the labor or services of a person by any one of, or by . . . means of force.” 18 U.S.C. § 1589(a)(1). The subsequent sections of the statute prohibit other labor practices that can be characterized as coercive, as opposed to forced. See, e.g., id. at § 1589(a)(4) (prohibition against “any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause the person to believe that, if that person did not perform such labor or services, that person or another person would suffer serious harm or physical restraint”). While forced and coercive labor practices differ, they are both encapsulated in this statute and referred to in Alejandro Menocal v. The GEO Group, Inc., Civil Action No. 14-cv-02887-JLK (D. Colo. Feb. 27, 2017) (Order Granting Motion for Class Certification Under Rule 23(b)(3) and Appointment of Class Counsel Under Rule 23(g) (EFC No. 49)), available at http://deportationresearchclinic.org/Menocal-Et-Al_v_GEO_Cert-2-27-2017.pdf.

- This is no mere conjecture. With year-over-year data now available, there is a re- corded increase in deaths within private prison populations. Justin Glawe, Immigrant Deaths in Private Prisons Explode Under Trump, daIlY BeaST (May 30, 2017, 1:00 AM), http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2017/05/30/immigrant-deaths-in-private-prisons-explode-under-trump.

- See OFFICE OF MGMT. & BUDGET, EXEC. OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT, AMERICA FIRST: A BUDGET BLUEPRINT TO MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN, FISCAL YEAR 2018 (2017), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/ fy2018/2018_blueprint.pdf (In March 2017, the 2018 Budget Proposal recommended an increase of $1.5 billion for “expanded detention, transportation, and removal of illegal immigrants.”). See also Daniel M. Kowalski, GEO Group Gives Money to Trump, Gets $110M Immigration Prison Contract, LEXISNEXIS LEGAL NEWSROOM IMMIGRATION LAW (Apr. 21, 2017, 12:44 PM), https://www.lexisnexis.com/legalnewsroom/immigration/b/ outsidenews/archive/2017/04/21/geo-group-gives-money-to-trump-gets-110m-immigra- tion-prison-contract.aspx?Redirected=true (In April 2017, the Trump Administration awarded a $110 million immigration prison contract to GEO Group to build a 1000-bed immigration prison facility in the same town outside Houston where it already has one., where the facility is expected to “generate $44M in annualized revenues.”); Mirren Gidda, Private Prison Company GEO Group Gave Generously to Trump and Now Has Lucrative Contract, NewSweek (May 11, 2017, 5:00 AM), http://www.newsweek.com/geo-group-private-prisons-immigration-detention-trump-596505.

- Staff of Bureau of Justice Statistics, Bulletin: Prisoners 1925-81, U.S. DEPT. OF JUSTICE (Dec. 1982), available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p2581.pdf.

- Id.

- See The CCA Story: Our Company History, CCA, http://www.cca.com/our-history (last visited July 9, 2017).

- See GEO Group History Timeline, GEO, https://www.geogroup.com/history_timeline (last visited July 9, 2017).

- See The CCA Story, supra note 8.

- See GEO Group History Timeline, supra note 9 (like CXW, GEO was hired to build “the Aurora Processing Center, providing secure care, custody, and control of 150 im- migration detainees” for the INS in Aurora, Colorado).

- STEPHANIE MINOR-HARPER & ALLEN BACK, BUREAU OF JUSTICE STATISTICS, U.S. DEPT. OF JUSTICE, PRISONERS IN STATE AND FEDERAL INSTITUTIONS ON DECEMBER 31, 1984 (Feb. 1987), available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/psfi84.pdf.

- at 1.

- Danielle Kaeble & Lauren Glaze, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015, u.S. depT. of JuSTICe (Dec. 2016), available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus15.pdf.

- IBISWORLD, CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES IN THE US: INDUSTRY REPORT 56121 (Nov. 2016).

- Id.

- Developments in the Law: The Law of Prisons, 115 harv. l. rev. 1838, 1841 (2002).

- Id.

- CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES, supra note 15.

- Id.

- Banking On Bondage: Private Prisons And Mass Incarceration, ALCU, https://www. aclu.org/banking-bondage-private-prisons-and-mass-incarceration (last visited June 9, 2017).

- Citizens United v. Fed. Election Comm., 558 U.S. 310 (2010).

- Eduardo Porter, Corporations Open Up About Political Spending, N.Y. TIMES (June 9, 2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/10/business/corporations-open-up-about- political-spending.html.

- Banking On Bondage, supra note 21, at

- CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES, supra note 15, at 22.

- Private Prison Information Act of 2014, H.R. 5838, 113th Cong. (2014), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/5838/text.

- Id.

- Fredreka Schouten, Private Prisons Back Trump and Could See Big Payoffs with New Policies, USA TODAY (Feb. 23, 2017, 1:10 PM), http://www.usatoday.com/ story/news/politics/2017/02/23/private-prisons-back-trump-and-could-see-big- payoffs-new-policies/98300394/.

- Id.

- Cartoon by Khalil Bendib on Erin Rosa, GEO Group, Inc.: Despite a Crashing Economy, Private Prison Firm Turns a Handsome Profit, CORPWATCH, (Mar. 1, 2009), http://www.corpwatch.org/article.php?id=15308.

- Banking On Bondage, supra note 21, at

- See, e.g., Do Private Prisons Really Save Us Money? AFGE (July 29, 2016), https:// afge.org/article/do-private-prisons-really-save-us-money/.

- Cody Mason, Too Good to be True: Private Prisons in America, THE SENTENCING PROJECT (Jan. 2012), available at http://sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Too-Good-to-be-True-Private-Prisons-in-America.pdf.

- Banking On Bondage, supra note 21, at

- For example, in private immigration detention facilities, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) maintains office space for its personnel. In addition to processing detainee intake and conducting interviews, ICE personnel “should be systematically encouraged to report indications of deficiencies, errors, and particularly more serious abuses” by private prison staff and “should also assure that channels are clearly defined for detainees and their families and representatives to report such problems” when they arise. SEE HOMELAND SECURITY ADVISORY COUNCIL, REPORT OF THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PRIVATIZED IMMIGRATION DETENTION FACILITIES (2016), available at https://www. dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/DHS%20HSAC%20PIDF%20Final%20Report. pdf. But, ICE fails to properly monitor human rights abuses in private facilities. This leaves one to question whether it is possible for ICE to function as an independent entity that can be accountable for providing this check given that it is permanently located within the facility it is supervising.

- Banking On Bondage, supra note 21.

- Solomon Moore, Inmate’s Family Wins $42.5 Million Judgment, Y. TIMES, Apr. 10, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/10/us/10brfs-INMATESFAMIL_BRF.html.

- Emma Perez-Trevino, Beating Death Lawsuit Ends in Settlement, BROWNSVILLE HERALD (Jan. 7, 2010, 12:00 AM), http://www.brownsvilleherald.com/article_7d219672-6121- 569a-bb89-43f33119e6b4.html.

- Id.

- Rosa, supra note 30.

- Id.

- Id.

- For explanations of the impact of the lawsuit, see, e.g., Tess Owen, Forced Labor Dispute, VICE NEWS (Feb. 28, 2017), https://news.vice.com/story/detained-immigrants-suing- a-private-prison-company-over-forced-labor-move-forward-with-groundbreaking- class-action; Tchekmedyian, supra note 3.

- Alejandro Menocal v. The GEO Group, Inc., Civil Action No. 14-cv-02887-JLK (D. Colo. Feb. 27, 2017) (Order Granting Motion for Class Certification Under Rule 23(b) (3) and Appointment of Class Counsel Under Rule 23(g) (EFC No. 49)), available at: http://deportationresearchclinic.org/Menocal-Et-Al_v_GEO_Cert-2-27-2017.pdf.

- Kelly v. Wengler, Case No. 1:11-CV-185-S-EJL (D. Idaho Sep. 16, 2013), available at https://www.aclu.org/legal-document/kelly-v-wengler-memorandum-decision- and-order-finding-cca-civil-contempt?redirect=prisoners-rights/kelly-v-wengler- memorandum-decision-and-order-finding-cca-civil-contempt.

- Sec’y of Labor v. The GEO Group, Inc., OSHRC Docket No. 12-1381 (Occupational Safety and Health Rev. Comm’n Dec. 20, 2013) (Stipulation of Settlement), available at https://www.osha.gov/enforcement/cwsa/geo-group-inc-12202013.

- Id.

- Press Release, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Comm’n, GEO Group to Pay $140,000 to Settle Sexual Harassment Suit Filed by EEOC and ACRD (Apr. 29, 2013) (on file with author), available at https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/4-29-13. cfm.

- Thomas J Cole, Inmates Receive $4.6 Million in Settlements, ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL (June 29, 2016, 12:02 AM), https://www.abqjournal.com/799917/inmates-get-46m- in-settlements.html.

- Memorandum from the U.S. Dept. Justice Office of Deputy Attorney General, supra note 2. See also Commentary, U.S. Dept. of Justice, Phasing Out Our Use of Private Prisons (Aug. 18, 2016), available at https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/blog/phasing-out- our-use-private-prisons [hereinafter Phasing Out Our Use of Private Prisons].

- Phasing Out Our Use of Private Prisons, supra note 50.

- Memorandum from the U.S. Dept. Justice Office of Deputy Attorney General, supra note 2.

- Notably, however, the stock prices do not take into account other corporations that con- tract with them or otherwise benefit from governmental prison contracts. Nonetheless, the outlook for revenue growth in larger correctional facilities industry largely tracks the growth and stock price trajectory of CXW and GEO.

- Zapotosky, supra note 1.

- See, e.g., Robert Ferris, Prison Stocks are Flying on Trump Victory, CNBC (Nov. 11, 2016, 1:50 PM), http://www.cnbc.com/2016/11/09/prison-stocks-are-flying-on-trump- victory.html; Jeff Sommer, Trump’s Win Gives Stocks in Private Prison Companies a Reprieve, N.Y. TIMES (Dec. 3, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/03/your- money/trumps-win-gives-stocks-in-private-prison-companies-a-reprieve.html.

- Kowalski, supra note 5 and accompanying text; Gidda, supra note 5 and accompanying text.

- Some private prison business risks were discussed previously. SEE CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES, supra note 15.

- Ashley Southall, Justice Dept. Joins Calls for Drug Sentencing Reform, N.Y. TIMES BLOG (Apr. 29, 2009, 3:41 PM), https://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/04/29/justice-dept-joins-calls-for-drug-sentencing-reform/.

- Prison Privatization, CUSA CORRECTIONS S.A., http://www.cusa.org/benefits.html (last visited July 10, 2017).

- Id.

- Gov. Code §§ 814-895.

- In turn, the government’s appropriation of the private correctional facility budget will correspond with investor confidence in CXW and GEO and their potential for continued growth. Thus, CXW, GEO, and other private prison corporations’ current growth may be shortlived.

- Stephanie Chen, Larger Inmate Population is Boon to Private Prisons, WALL ST. J. (Nov. 19, 2008, 12:01 AM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB122705334657739263.